By Leslie M. Mitchell, ’81

In 1998, The New York Times called Helen Wills, “arguably the most dominant tennis player of the 20th century and the first American-born woman to reach international celebrity as an athlete.” It is hard to argue with that assessment. University of California alumna Helen Wills was the greatest woman tennis player in the world in the 1920s and 1930s. She won two Olympic Gold Medals and 31 Grand Slam titles. Her eight Wimbledon singles titles stood as a record for more than 50 years. She was the number one ranked women’s tennis player in the world for eight years between 1922 and 1933, and had she not been kept out of action by a series of back injuries, she would have been ranked number one even longer. From 1927 to 1933, Wills won 180 straight matches, including a 158-match streak in which she did not lose a single set. Her career record, from 1919 to 1938, was 398-35, a .919 winning percentage. And when silent film star Charlie Chaplin was once asked to describe the most beautiful thing he had ever seen, he famously replied, “Helen Wills playing tennis.” Helen Wills was truly one of the greatest athletes in the history of the University of California.

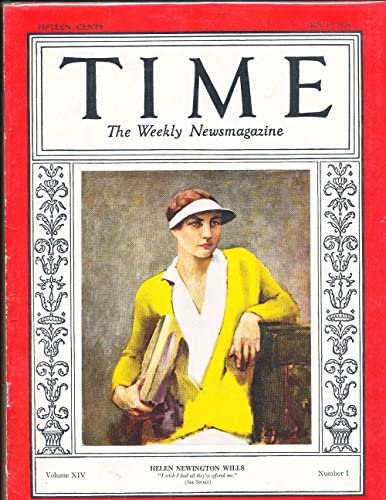

Helen Wills on the cover of the July 1, 1929 issue of Time Magazine, wearing her trademark visor.

Helen Wills was born in Centerville (now Fremont), California on October 6, 1905, and grew up in Berkeley. For her fourteenth birthday, her parents gave her a membership in the Berkeley Tennis Club, and she began tennis lessons. In 1920, while playing at the Berkeley Tennis Club, she met Hazel Hotchkiss Wightman, four-time winner of the US Championships (now known as the US Open). Wightman, a 1911 Cal graduate, was visiting her parents in Berkeley from her home in Massachusetts. She was immediately impressed with the 15-year old Wills, and became her coach. The following year, 1921, Wills won the national junior tennis championship. And the year after that she won the US Championship at the age of 17.

15-year-old Helen Wills playing in her first US Junior Championship tournament.

The same year that she won her first US championship, Wills entered the University of California. In her memoirs, Wills described herself as an overly serious young woman who thought most of the fun of college life to be a waste of time. The serious Wills determined that, while continuing her focus on tennis, she also wanted to be awarded a Phi Beta Kappa key. She found out what grade average was required and made that her goal. She described her pursuit of that goal this way:

“My attitude was not at all consistent with the meaning of the award as I have since regretted. I had a complete lack of interest in learning for the sake of knowing something. For two years I studied almost every night, never without a preliminary groan. Books relating to classes I opened with reluctance, I avoided all lectures which came in the afternoons, and kept away from the library. That seems to me now to have been a very peculiar way of seeking scholastic honors.”

Near the end of her freshman year at Cal, Wills was informed that she had been selected to be a member of the American team for the upcoming 1924 Olympics in Paris. Yet she was still concerned with her Phi Beta Kappa pursuit and, as she said in her memoirs, it was only “when I heard that I had an ‘A’ on my zoology paper that I felt I could face the Olympic tennis with a clear conscience.”

Since she was going to be in Europe that summer, Wills decided to go few weeks early and play at Wimbledon for the first time. She teamed up with her coach, Hazel Wightman, to win the women’s doubles championship in what was the Wimbledon debut for both the 19-year-old Wills and the 37-year-old Wightman. In singles, Wills reached the final, but lost that match. That was the last singles match Helen Wills would ever lose at Wimbledon.

Hazel Wightman and Helen Wills

Then it was on to Paris for the Olympics. Although the conditions were in many ways dreadful, Wills later said that she enjoyed her experience in Paris more than any other tournament in which she ever played. She felt less pressure than at Wimbledon and loved the city of Paris. But as for the conditions, she said, “if they had hunted for an uglier place for the games, it could not have been found.” The tennis courts had not even been laid or the stands built when the athletes arrived. “The dressing room for the women players was a large shed with a tin roof and had in it a shower that worked in only one needle. There was much complaint at the poor arrangements.” Wills also noted that the players could see the track and gymnastic events going on at the adjoining stadium, which could become quite distracting in the middle of a match. According to Wills:

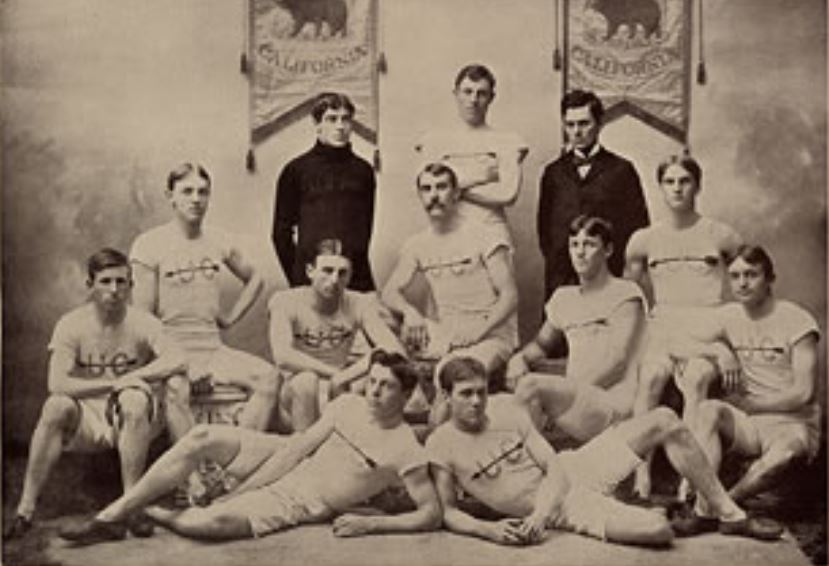

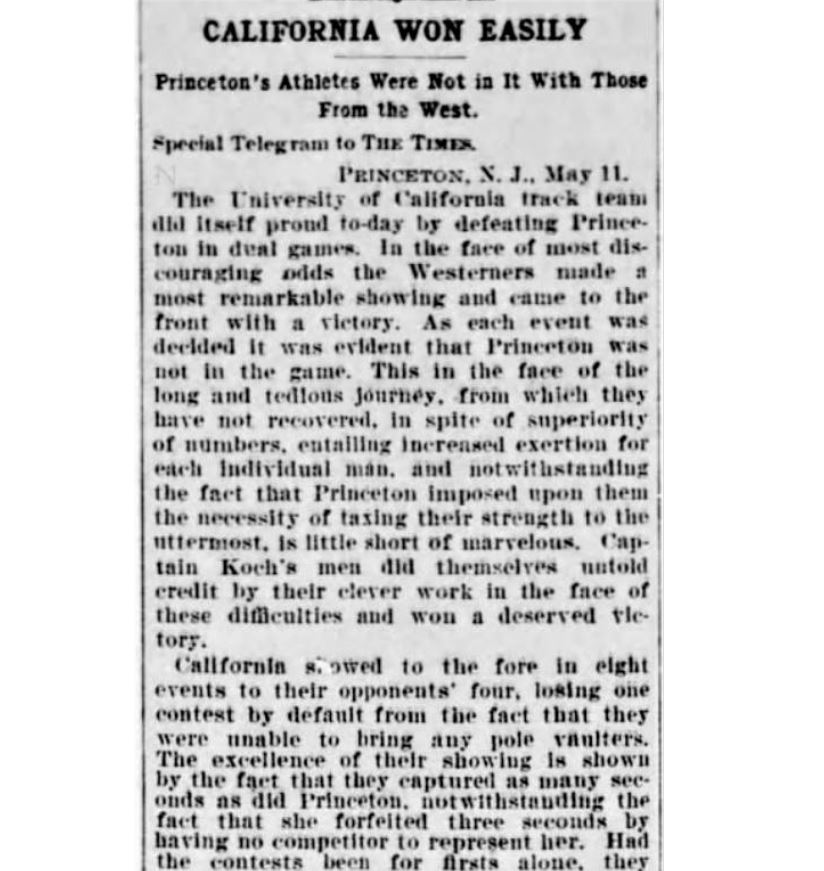

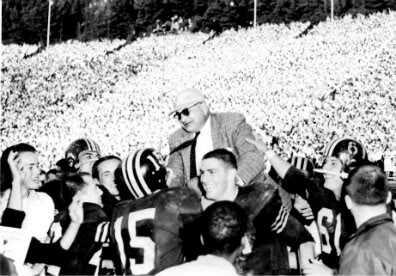

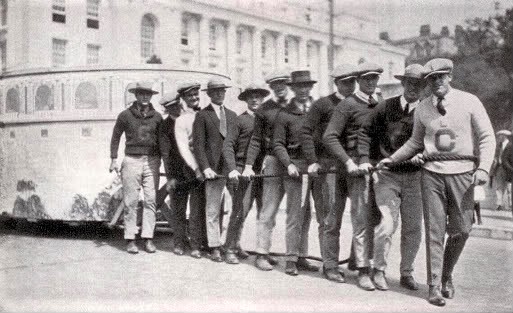

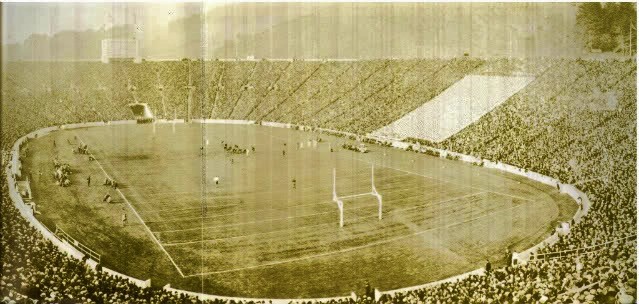

“When you were playing on a side court, where there was an uninterrupted view of the field, it was at times hard to keep your mind on the game. The gymnasts would get into extraordinary positions on the bars and stay there. When you looked up again after the end of a rally they would still be there immobile. The tumultuous shouting of the vast crowds in the big stadium would burst out just as you were waiting to hit an overhead, or at some other important moment. I glanced up during one match to see Walter Christie, the famous University of California track coach, leaning on the fence. He had brought the University of California team to the Olympic meet.”

Once again Wills and Wightman teamed up for doubles. They won every match easily to secure the Gold Medal for the United States. But the event tennis fans had been looking forward to was a match between Helen Wills, the young American champion, and the French champion, Suzanne Lenglen, who was universally regarded as the best player in the world. But Lenglen dropped out of the Olympics at the last moment, as she had done at Wimbledon a few weeks earlier. There was much speculation that she wanted to avoid playing Wills. Lenglen claimed to have jaundice. The American coach tartly responded that she certainly seemed yellow.

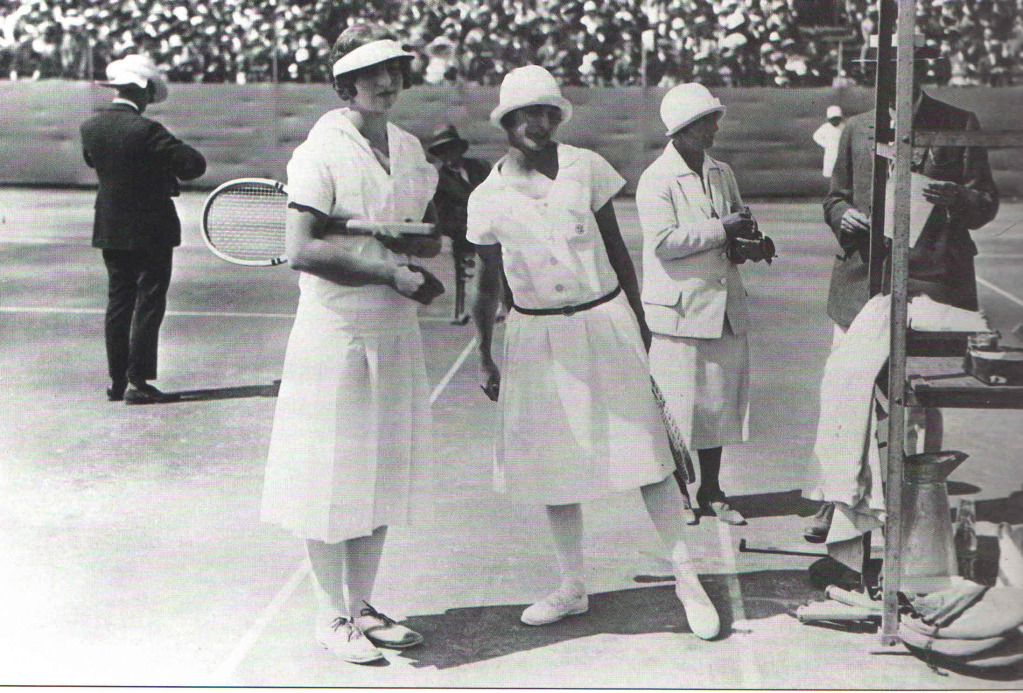

Helen Wills, left, with Didi Vlasto, just before the Gold Medal match at the 1924 Olympics.

Wills ended up playing another French player, Didi Vlasto, in the Gold Medal match. Even at 19, Wills was a master strategist. Faced with Vlasto’s strong forehand, Wills fed high balls with considerable top spin to Vlasto’s backhand, drawing her far off the court. Then, with Vlasto out of position, Wills hit hard forehand winners. The French crowd began booing, and calling out that Wills was taking unfair advantage of Vlasto’s weakness. However, Wills was not without supporters of her own. As Wills later wrote:

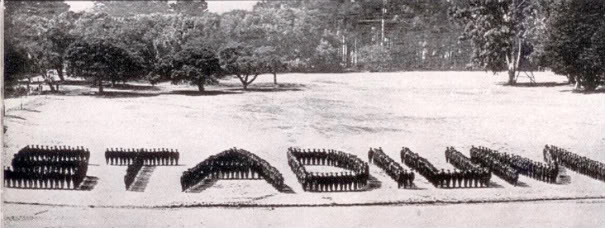

“Just as we were about to play, a group of University of California students and some of the track team, who I didn’t know were there, stood up and gave a University of California cheer which began “Oski-wow-wow!” I understood it as encouragement, but Didi Vlasto did not know what in the world to make of it. She started off no doubt with a handicap because of this, and it was several games before her drives began to find the lines.”

In the end, Wills won the match easily, 6-2, 6-2, and earned her second Gold Medal of the games. Together, Helen Wills and Hazel Wightman won all the women’s tennis events at the 1924 Olympics, with Gold in singles and doubles for Wills, and in doubles and mixed doubles for Wightman. They were the first women athletes from Cal to win Olympic Gold and, indeed, the first to compete at the Olympics. And they remained the reigning Olympic champions in their events for 60 years, as the sport of tennis was dropped from the Olympics after 1924, and did not return until 1984.

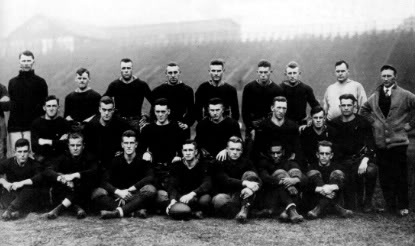

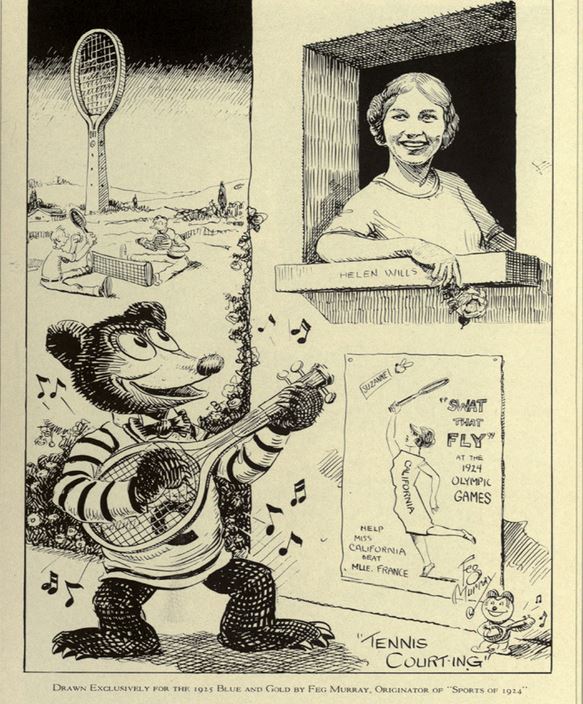

The 1925 Blue & Gold Yearbook celebration of Helen Wills’ Olympic Championships.

Wills returned to Berkeley after the Olympics for her sophomore year at Cal. Two years later she was duly awarded the Phi Beta Kappa key on which she had set her sights. In the meantime, she returned to Wimbledon in 1925 where, in her second try, she won the first of what would become an extraordinary eight singles titles.

Wills’ increasing fame led to calls for a match with Suzanne Lenglen, the other great woman player of the time. It seems clear that Lenglen wanted to avoid playing Wills but finally in 1926, under intense pressure, she agreed to an exhibition match to be played in France. The match was the tennis event of the decade. It was described as having a “prizefight atmosphere,” with tickets being scalped for the outrageous sum of $50. The match itself had some bizarre moments. Wills lost the first set 6-3, but had a set point in the second. A disputed line call cost her that set point and, for the only time in her career, the stoic Wills showed strong emotion on the court, raising her voice to argue with the linesman – to no avail, of course. Then, when Lenglen had match point, Wills’ ball was called out, and the match was over. The players met at the net to shake hands. But in the midst of the celebration by the French fans, the umpire made his way through the crowd to say that he had called the ball good. The “out” call had been made by someone in the stands. Angry fans were cleared off the court, and the match resumed. Ultimately Lenglen prevailed, but it took her three more games.

Thinking the match over, Lenglen and Wills shake hands, as an official signals that it is not over, after all.

Lenglen, knowing when to leave well enough alone, refused a rematch, and the two tennis greats never played again. For her part, Wills took the loss stoically, and later said that it had taught her the need to add more nuance to her game. In fact, the very shy and reserved Wills was famous throughout her career for her utterly unflappable demeanor on the court. She showed so little emotion that she was nicknamed “Little Miss Poker Face.” Her concentration was legendary. She claimed to be unaware of game points, set points and even match points. Her mantra was, “Every shot, every shot, every shot.” Crowds did not like her apparent aloofness, and she was often called “Queen Helen” or “Imperial Helen.” But Wills explained, “I had one thought and that was to put the ball across the net. I was simply myself, too deeply concentrated on the game for any extraneous thought.”

Denied a great rivalry with Lenglen, Wills ultimately found the biggest rival of her career very much closer to home. Helen Jacobs, who was a few years younger than Wills, also grew up in Berkeley and attended the University of California and, like Wills, was coached by fellow Cal alum Hazel Wightman. The Wills and Jacobs families were acquainted through their memberships in the Berkeley Tennis Club. When Helen Wills was 19, her parents had a new home built on Tunnel Road and sold their Shattuck Avenue house to the parents of 15-year-old Helen Jacobs. Thus, the two future rivals were not only both Cal alums, but also spent their high school years living in the same house.

Cal alums Helen Wills and Helen Jacobs entering Centre Court at Wimbledon.

Wills was always the greater player. Wills and Jacobs met in the finals of Grand Slam tournaments seven times. Although their matches were almost always close and exciting, Wills won every match, until the finals of the 1933 US championship. On that occasion, Jacobs won the first set 8-6. This caused quite a stir in the crowd, as losing even a set was highly unusual for Wills. She came back to win second set. But in the third set, Jacobs took a 3-0 lead. Wills then told the umpire that she was unable to continue because of back pain. This created a huge controversy, as some fans believed that Wills had defaulted only to avoid what appeared to be a certain loss to Jacobs. Wills always insisted she had been genuinely suffering from a debilitating back injury. The incident fed stories of a feud between “The Two Helens” as they were known in the press. In fact, it appears that while they never became friends, there was no feud. They were simply very different personalities, with Wills being ever reserved and intensely focused, while Jacobs was far more gregarious and outgoing. Hazel Wightman, who was a coach, mentor, and friend to both of “the Helens” described Wills this way: “Helen was really an unconfident and awkward girl — you have no idea how awkward…. I thought of Helen as an honestly shy person who was bewildered by how difficult it was to please most people.”

Although she did not win Wimbledon in 1933, Wills did win another remarkable match that year. Forty years before the famous Billie Jean King vs. Bobby Riggs “Battle of the Sexes,” Wills played an exhibition against Phil Neer, a former Stanford tennis star and the eighth-ranked men’s tennis player in the United States. She beat him 6-4, 6-4.

Although she remained an amateur throughout her career, Wills made a substantial fortune from writing newspaper columns and books about tennis, and from endorsements. She also turned her fine arts studies at Cal into a lucrative second career as a painter.

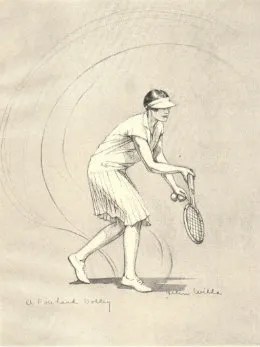

A sketch by Helen Wills of herself, demonstrating a forehand volley. This and several other Wills’ drawings appeared in her 1928 book on how to play tennis.

Nagging back injuries hampered Wills’ tennis career in the mid-1930s, and she was unable to play for many months at a time during that period. She was finally forced to retire in 1938 at the age of 32. However, before her retirement, she came back for one final win at Wimbledon, once again besting her Berkeley rival Helen Jacobs in the final. 1938 turned out to be the most Blue and Gold year ever at Wimbledon. In addition to two Cal alums playing in the women’s final, another former Cal student and Berkeley Tennis Club member, Don Budge, won men’s singles, men’s doubles and mixed doubles that year.

In her career, Helen Wills had won, in addition to two Olympic Gold Medals, a total of 31 Grand Slam titles. Although her career was interrupted and shortened by injuries, in a period of 15 years she won 19 Grand Slam singles titles: eight Wimbledon titles, seven US titles, and four French titles. She never played in the Australian, which was technically a Grand Slam at that time, but generally avoided by the top players due to the long sea voyage involved in reaching it. Wills also won 12 Grand Slam doubles and mixed doubles titles with eight different partners. In her entire career, she never failed to reach the finals of any Grand Slam tournament in which she played, except for two tournaments in which she had to default due to injury. Helen Wills’ eight Wimbledon single titles was the most by any player, man or woman. That record stood for more than 50 years, until Martina Navratilova won a ninth singles title in 1990. And Navratilova is still the only player to equal or exceed Wills’ record.

Helen Wills was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1959, the Cal Athletic Hall of Fame in 1978 (Wills and Hazel Wightman were the first two inductees), the Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame in 1981, and the Intercollegiate Tennis Association Women’s Hall of Fame in 1996. She died at her home in Carmel, California on January 1, 1998, at the age of 92. Although she had married twice, first to Frederick Moody, whom she met at her match with Suzanne Lenglen, and later to polo player Aiden Roark, she had no children. She left her $10 million estate to the University of California to found the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute in Berkeley. The Institute currently has a faculty of over 50 researchers and administers the University’s graduate program in neuroscience.

In 1984, when Tennis returned to the Olympics after an absence of 60 years, the 78-year-old Helen Wills sent this message to each member of the US Olympic Tennis Team on the first day of competition:

“On this day that welcomes the return of Tennis as an Olympic sport, though I am not present for the occasion, I am there in my thoughts, and join you all in welcoming the return of the game we love so much to the competition that it so well deserves. At this moment, my thoughts go back to July 1924, in Paris, the last time tennis was included in the Olympic Games. Using the word ‘last’ once more, I, the last member of our Olympic Team who is still living, am so happy to extend a message that I believe would be expressed by each member of our 1924 Olympic Team: We are very happy not to be remembered as the “last team” – We now belong to the future. Our message to all future contestants is to carry on proudly the Olympic Tradition of Sport for all Nations – In Peace, Helen Wills Roark, 1984″

GO BEARS!

____________________________

Sources

Englemann, Larry, The Goddess and the American Girl: The Story of Suzanne Lenglen and Helen Wills, Oxford University Press, New York (1988)

Finn, Robin, “Helen Wills Moody, Dominant Champion Who Won 8 Wimbledon Titles, Dies at 92,”The New York Times (January 3, 1998)

King, Billie Jean & Starr, Cynthia, We Have Come a Long Way: The Story of Women’s Tennis, McGraw-Hill, New York (1988)

Lumpkin, Angela, Women’s Tennis: A Historical Documentary of the Players and Their Game, The Whitston Publishing Co., Troy, New York (1982)

Phillips, Ellen, The VIII Olympiad, World Sport Research & Publications, Inc., Los Angeles (1996)

Wills, Helen, Tennis, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York (1928)

Wills, Helen, Fifteen-Thirty: The Story of a Tennis Player, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York (1937)

Yeomans, Patricia Henry, “Hazel Wightman and Helen Wills: Tennis at the 1924 Paris Olympic Games,” Journal of Olympic History, Vol. 11, No. 2, International Society of Olympic Historians (June 2003)