Who is the only person who ever coached teams to both the Rose Bowl and the Final Four? The University of California’s Clarence “Nibs” Price. Nibs Price took over as Cal’s football head coach in 1926, after the death of Andy Smith. In his five years as head coach, he had three tremendous seasons and took the Bears to the 1929 Rose Bowl — where they were involved in one of the most famous (or infamous) plays in football history. And at the same time Price was coaching the football team, he was also the basketball head coach, ultimately winning more games than any coach in California basketball history, and earning a trip to the Final Four in 1946.

Clarence M. “Nibs” Price was born in San Diego in 1890. In 1910 he was admitted to the University of California in Berkeley where, despite his short stature and slight build, he earned a varsity letter in rugby as well as baseball. He would have liked to have played football as well, but this was the era when American football had been replaced by rugby at Cal. After graduating in 1914, Price returned home to San Diego, where he became the football coach at his alma mater, San Diego High School, until he joined the Army Air Corps to serve in World War I.

Price was discharged from the service in Seattle in December 1918. On his way home to San Diego, he stopped off for a visit in Berkeley, where he met the new California head coach, Andy Smith. Smith was looking for an experienced football coach to take over the Bears’ freshman team. There was not a lot of talent to choose from, because most west coast high schools had given up American football in the early 1900s, as a result of the extreme violence, injuries, and even deaths resulting from the sport. California itself had only returned to playing football in 1915. But San Diego High was one of the few schools which had never stopped playing the game. Smith thought Price would be good for Cal, both as an experienced football coach and as someone who might be able to convince the talented players at San Diego High and other football schools to come to Cal. Price jumped at the chance to return to Berkeley, and was hired as an assistant coach on the spot. He would remain a Cal coach for the next 35 years.

Hiring Nibs Price was one of the smartest decisions Andy Smith ever made, because Price turned out to be a great recruiter. He convinced several of the best players he had coached in San Diego to come to Cal, among them Stan Barnes and Harold “Brick” Mueller, two of the greatest ever to play at Cal. Price was also on good terms with coaches and players from other southern California high schools, against whom he had competed. He was able to use those personal ties to recruit Archie Nisbet, Don Nichols, Bill Bell and others to play for him on the Bears’ 1919 freshman team. The following year, it was these Nibs Price recruits who became the heart of California’s “Wonder Teams.”

The Wonder Team set college football ablaze in 1920, with a perfect 9-0-0 record, including a dominating 28-0 win over Ohio State in the Rose Bowl. The team was undefeated again in 1921, and then again in 1922, establishing California as one of the great football powers in the nation. So great was the Wonder Team’s success, that Cal built a spectacular new stadium to hold the enormous crowds clamoring for tickets.

Even after the first group of Wonder Team players graduated, the Bears continued to have great success under Andy Smith and his staff, completing two more undefeated seasons in 1923 and 1924. Things dropped off in 1925, with a decline in talent. The Bears went 6-3, suffering their first losses in six years. Still, Cal fans had unwavering faith that Andy Smith would return the Bears to glory within a year or two. But it was not to be. While on a visit to Philadelphia in January 1926, the 42-year-old Smith contracted pneumonia and died suddenly.

Andy Smith had stated several times that he thought Nibs Price was his natural successor as Cal’s head coach, and Price was duly elevated to that position in March 1926. Following the incomparable Andy Smith, especially in light of his sudden and shocking death, was an almost impossible task. To make things even more difficult for Price, he had also been named as Cal’s head basketball coach the previous year, and would now be responsible for coaching both teams.

The 1926 football season was not a promising start for Price’s Bears. The team had lost all its best players to graduation and it would probably have been a “re-building” year even if Andy Smith were still the head coach. Added to that, Smith’s death had cast a pall over the team, the fans, and the season. The Bears’ record was 3-6 — Cal’s first losing season in American football since 1897. (The Bears did have a losing season in 1906, during the period when rugby had replaced football.) The season ended with a dismal 41-6 loss to undefeated Stanford. But despite the team’s problems in 1926, Nibs Price had the full support of his team and of Cal fans, who recognized what a difficult task he had. In fact, Cal set an all-time attendance record that year, with 417,000 fans showing up at California Memorial Stadium to watch the Bears.

The fans’ confidence in Price was rewarded. The 1927 team, made up of now-experienced upperclassmen and a group of excellent sophomores newly elevated from the freshman team, made a much stronger showing. The season started with a 14-6 win over Santa Clara sparked by the surprising passing of unknown sophomore Benny Lom. The next week the Bears handed Nevada a resounding 54-0 defeat. Lom’s passing was the key again to Cal’s upset of St. Mary’s, and a 16-0 defeat of Oregon. The Bears were 5-0 going into the game against heavily favored USC in Los Angeles. The Trojans pulled out a 13-0 win, but the press called it one of the hardest-fought contests in memory. The Bears also lost to Stanford, but the 13-6 score was at least nowhere near as embarrassing as the prior year’s rout. Cal finished the season with a rare inter-sectional game against Pennsylvania, which was also highly favored. Price called plays which were very wide-open by the standards of the day, including a 40-yard pass from Benny Lom to Jim Dougery, resulting in a touchdown. Late in the game, Price called for a real razzle-dazzle play, with Paul Clymer throwing a pass to Paul Perrin, who then lateraled to Lee Eisen, who ran 42 yards for another touchdown. The stunning 27-13 Cal victory ended a successful 7-3 season that showed the Bears were back.

1928 would prove to be one of the most memorable seasons in Cal football history. Although the offense was a bit suspect, Price had a defense that was almost impenetrable. The Bears began the season with wins against Santa Clara, St. Mary’s, and Washington State, before facing a big test in the high-scoring USC team. A capacity crowd of more than 81,000 in Berkeley saw the Bears and the Trojans battle to a 0-0 tie. The star of the game was once again Benny Lom — but this time because of his outstanding punting! It was the first time USC had been shut out under head coach Howard Jones, and the Bears were pleased with their effort.

The 1928 Bears were 6-1-1 going into the Big Game against another very high-scoring team. Once again the Cal defense came up strong, the big play being an interception and 75-yard run-back by Steve Bancroft for a Cal touchdown. The Bears were leading 13-7 late in the game, when disaster struck. With seconds left in the game, Stanford had the ball on Cal’s 24. Stanford quarterback Bill Simkin threw a bad pass, which Cal’s Irv Phillips could easily have intercepted. But Phillips thought it was fourth down, and just batted the ball down. On the next play, Stanford scored a touchdown to make the score 13-13. But the snap for the extra point was slow, giving Cal’s Frank Fitz time to smash through the Indians’ line and block the kick. The game ended in a tie. While this was certainly not as satisfying as a win, it was enough to send the 6-1-2 Bears to the Rose Bowl on New Year’s Day.

The 1929 Rose Bowl between California and Georgia Tech turned out to be one of the most talked-about football games of all time. Once again, Cal’s defense was outstanding. And statistically, the Bears were ahead in every category, leading George Tech in: first downs 11-5; rushing yards 204-166; and passing yards 67-23. The only place Georgia Tech prevailed was the final score: 8-7. It was in this game, of course, that Cal’s Roy Riegels picked up a Georgia Tech fumble and started running toward the end zone. But Riegels had become confused and turned around, and he began running toward the wrong end zone. Teammate Benny Lom chased Riegels down the field, shouting at him to turn around, but he could not be heard over the roar of the crowd. Lom finally caught Riegels and tackled him on the Bears’ one-yard line.

Although California had the ball first-and-ten on their own one-yard-line, the stunned Nibs Price ordered a punt on the next play. Calling a punt on first down was a fairly extraordinary thing to do, and Price’s call has remained highly controversial ever since. He was concerned that the Bears had been so demoralized by the Riegels play, they might easily give up a safety on the one-yard line. And the Cal defense was so outstanding that he was confident they would not give up a score if they could just get a little room from a punt. But Price’s decision to punt only piled disaster onto disaster. The punt was blocked and rolled out of the end zone for a Georgia Tech safety — the very thing Price had been trying to avoid. And that safety that would turn out to be the margin of victory for Georgia Tech.

Roy Riegels was in a state of shock. Price did not want to remove him from the game, (he would not be allowed to come back in until after the half under the rules of the day), because he believed it would be a terrible blow to team morale. But he could not determine whether Riegels was injured or merely stunned by what had happened. So he took Riegels out and the young man sat on the bench trying to hold back tears as his teammates attempted to comfort him.

At halftime, Coach Price had to decide what to do with the devastated Riegels in the second half, as the young man sat sobbing in the corner of the locker room. Shortly before half-time ended, Price announced, “Men, the same team that played in the first half will start the second.” As the players started to run back onto the field, Riegels remained sitting where he was. When Price again told him he was going to start the second half, Riegels said, “Coach, I can’t do it to save my life. I’ve ruined you, I’ve ruined the University of California, I’ve ruined myself. I couldn’t face that crowd in the stadium to save my life.” Price put his hand on Riegels’ shoulder and said, “Roy, get up and go on back; the game is only half over.” And Riegels went out and played and played an outstanding second half.

Unfortunately, Cal was not able to pull out the win, and Riegels become known forever as “Wrong Way Riegels.” However, Price’s vote of confidence in Riegels would pay off the following year, when he was elected captain by his teammates and named a first team All-American. And for the rest of his life, Roy Riegels made a point of sending letters to high school and college athletes who had made blunders which cost their teams a game, offering comfort, and letting them know that making such a mistake was not the end of the world.

Despite the great disappointment of the Rose Bowl loss on January 1, the 1929 football season would be Nibs Price’s best. The highlight of the year was once again the USC game. And that game once again showed off Price’s willingness to take risks, when he called a fake punt from Cal’s own 15 yard line. Punter Benny Lom pulled the ball down and cut around the Trojan defender, who was blocked by Rusty Gill. Lom then dodged right between two more USC defenders, and ran 85 yards for the touchdown. A couple of series later, Roy Riegels blocked a Trojan punt through the end zone for a Cal safety. The final score was California 15, USC 7. Once again, the victory was won despite mediocre offense (USC out-gained the Bears 252 to 192, and the Bears punted 13 times), because of outstanding defense and Price’s gamble on special teams.

Although Cal ended the 1929 season with a 7-1-1 record, it was not entirely satisfying, because the one loss once again came against Stanford. A victory, or even a tie in the Big Game would have sent the Bears back to the Rose Bowl. But as it was, California, Stanford, and USC ended the season tied for the conference championship. In light of the Bears’ 21-6 loss in the Big Game, University President William Campbell withdrew Cal from consideration for the 1930 Rose Bowl, and USC was given the bid.

The Bears had a Rose Bowl and a combined 20-6-3 record over the 1927-1929 seasons under Price. But virtually all of their great players graduated at the end of the 1929 season, including Benny Lom and first team All Americans Roy Riegels and Bert Schwarz. Even worse, 1930 began with a very bad omen when Stanford students disguised as reporters stole the Axe and spirited it away to Palo Alto.

The 1930 Golden Bears started the season a mediocre 3-3. And then thing got much worse. USC decided to take revenge for their loss the previous year and utterly demolished the Bears, 74-0, running up 734 yards of total offense. 95 years later, this game remains the worst loss in California history. An unfavorable editorial in The Daily Californian stirred up a media frenzy about the students trying to have Nibs Price fired. In fact, most students and fans still supported the coach, who had just completed three successful seasons. It was even reported in the papers that a prominent supporter of Coach Price had said, “Let’s face it, fellows. We were beaten 74-0 by the best professional football team in the country.” The president of USC expressed outrage at this comment and threatened to break off all relations with the University of California, until Cal’s president, Robert Gordon Sproul, intervened to smooth things over.

But the debacle against USC had definitely had consequences for the Bears. The next week, only 3,000 fans showed up at Memorial Stadium to watch Cal defeat a weak Nevada team 8-0. And the seemingly dispirited Bears were then crushed 41-0 by Stanford. The Bears’ record on the season was only 4-5, but Nibs Price resigned as head coach two days after the Big Game.

Nibs Price’s career record as Cal’s head coach was 27-17-3. Three of his five seasons were highly successful, and he took the Bears to the 1929 Rose Bowl. His less-than-stellar rookie year can be attributed to the shock of Andy Smith’s death, and the graduation of many of the Bears’ best players. The loss of key players was also a big factor in the unsuccessful 1930 season, although the blow-outs by USC and Stanford were embarrassing. Yet there is no reason to think that Price could not have turned the team around if he had remained as head coach. He had a good group of new recruits coming in for 1931 and, in fact, the 1931 team would go 8-2, including a 6-0 victory over Stanford.

It was entirely Price’s decision to resign as head coach. But he was by no means done at his beloved alma mater. Price actually remained on the football staff as an assistant under the new head coach, Bill Ingram, and under Ingram’s successors, including Stub Allison and Pappy Waldorf, coaching defensive backs and punters. Under Waldorf, he became the Bears’ head scout. Price’s football knowledge and recruiting abilities remained an important part of the Cal program for another 24 years. As a result, Nibs Price coached for seven of California’s eight Rose Bowl teams: in 1921 and 1922 as an assistant to Andy Smith, in 1929 as Cal’s head coach, in 1938 as an assistant to Stub Allison, and in 1949, 1950, and 1951 as an assistant to Pappy Waldorf.

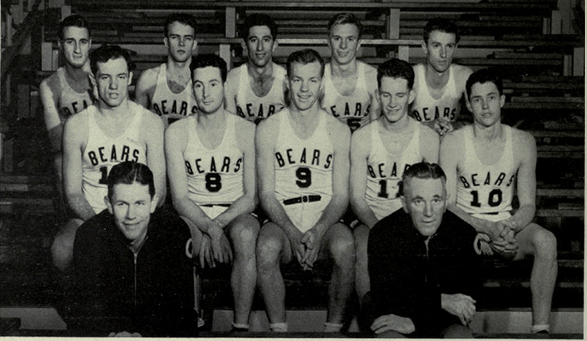

In the meantime, Price had also been serving as Cal Men’s Basketball’s head coach since 1924. Basketball was considered a minor sport in these years, and it was not unusual for college coaches to double up on sports. And in basketball, Price had spectacular success. There was considerable doubt when he was made head coach, because he had virtually no background in the sport, but he led the Bears to three straight Pacific Coast Conference championships in his first three seasons, 1924-1927, compiling a 42-4 record. The Bears won the Pacific Coast Conference title again in the 1928-1929 season, at the same time Price was leading Cal Football to the Rose Bowl.

Price served as Cal’s Men’s Basketball head coach for an astonishing 30 seasons, from 1924 to 1954, during which time the team won eleven conference championships. The 1926-1927 team went 17-0. The NCAA Tournament did not exist until 1939, and there was no other national playoff or championship tournament before then. However, the 1926-1927 Golden Bears have been retrospectively named as that year’s National Champion by the Premo-Porretta Power Poll.

In 1946, Price led the Bears to the Final Four, following a 30-5 season and another first place finish in the Pacific Coast Conference. They were eliminated in the National semi-final by Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State), which went on to win the National Championship. Price’s career record as Cal’s basketball coach was 449-294, and his 449 career wins remains the Cal record. When he finally retired in 1954, it was Price who urged the University to hire the University of San Francisco’s basketball coach, Pete Newell, to succeed him. He remained an avid follower of Cal sports, offering advice and support to his successors.

Nibs Price had a truly remarkable career at Cal, as a student, a rugby and baseball player, and a football and basketball coach, spanning a period of more than 40 years. Coaching teams to both the Rose Bowl and the Final Four and winning conference champions in both football and basketball in the same year are feats that it is safe to say will never be equaled, given the modern landscape of college athletics.

GO BEARS!