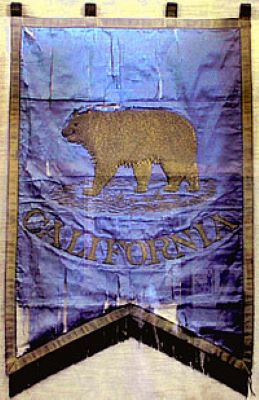

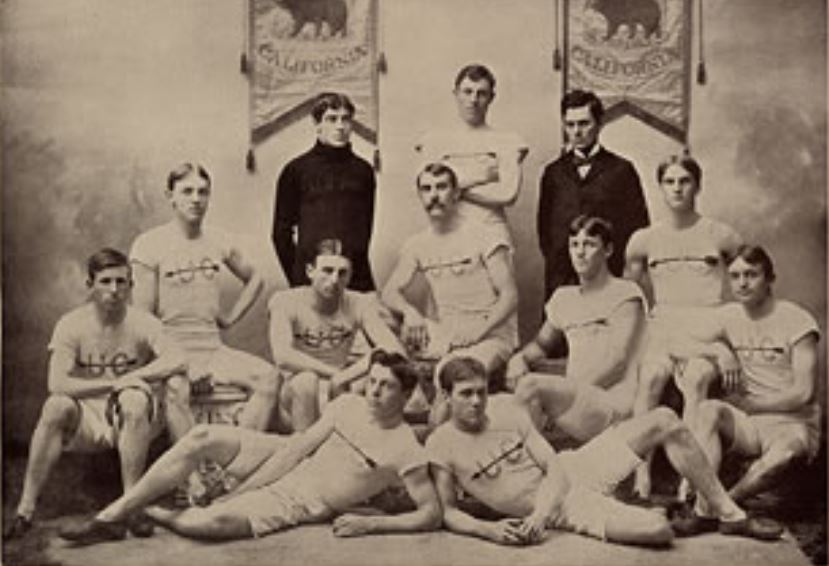

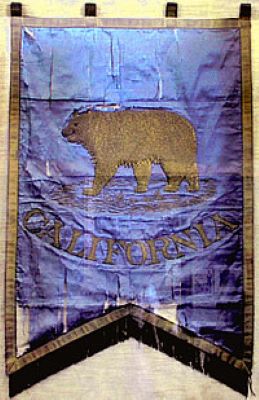

On May 2, 1895, eleven members of the California Track and Field team boarded a train at the Berkeley station on Shattuck Avenue and departed for the east coast to take on some of the great powerhouses of American track. No western team had ever traveled so far or competed against the highly regarded eastern schools, or against any eastern school at all. Indeed, none of California’s athletic teams had ever even traveled outside their home state before. The team carried with them two blue banners, each with a gold colored bear embroidered on it, along with the word “California,” also in gold. When the California team left Berkeley, the papers referred to them by their established nickname, “the Blue and Gold.” By the time they returned, after having shocked the east with their athletic prowess, the team – and the entire University – had become “the Golden Bears.”

In the 1890s, Track and Field was one of the major college sports, second only to football and more or less tied with baseball in popularity and importance. The idea of an east coast trip by the California team had been percolating around the Berkeley campus since at least 1893. In 1894, the idea was brought before the students – who at that time both funded and controlled the athletics programs – by team captain Fred Koch and the faculty advisor, George C. Edwards. Edwards was a member of the Class of 1873, the University’s first graduating class, and a math professor. Cal’s track stadium, Edwards Stadium, would later be named in his honor.

The students present when the eastern tour was proposed voted unanimously in its favor. Professor Edwards and students Koch, H. H. Lang, M. Anthony and Arthur W. North were given sole charge of organizing the trip. They held a mass meeting of students, and according the the Blue and Gold Yearbook report, within 20 minutes, the students had put up over $1,000, a large sum at the time and almost one-third of what would turn out to be the total cost of the trip. The Committee selected eleven athletes to make the trip and began arranging for training for the team and continued raising funds. Telegrams were dispatched to eastern schools and team manager Arthur North set off by train to talk to the schools about organizing competitions. He returned to Berkeley with commitments from Princeton, the University of Pennsylvania, Union College in Schenectady, New York, the Chicago Athletic Association and the Denver Athletic Club. More competitions would be added, even while the team was traveling in the east.

There was great excitement when the team left Berkeley on May 2, 1895. Students and faculty had donated from their own pockets to fund the trip and they took a proprietary interest in the fate of the team. One of the athletes, Robert Edgren, was a standout in the hammer throw. He was also an aspiring writer, having been hired by William Randolph Hearst as a part time journalist for the San Francisco Examiner just a few months earlier. Hearst directed Edgren to write dispatches back to the paper regarding every development on the trip. Accordingly, Edgren spent many of his evenings during the trip writing articles about the contests which had taken place and his assessments of the upcoming meets and teams, and taking them down to the local Western Union office to oversee their dispatch by telegraph. Bay Area readers followed his reports and the team’s progress assiduously.

On the trip, the athletes tried to stay fit by getting off the train and running at every station where it stopped and by doing gymnastic exercises on the train itself. The Bay Area boys, used to the cool weather of a Berkeley summer, were shocked by the heat. Temperatures for most of the trip were in excess of 90 degrees, with the high humidity found in the East and Midwest. At least two players suffered so much from the heat that they were uncertain if they would be able to compete. The fatigued team arrived in Princeton, New Jersey at 3:00 a.m. on May 8, having spent six days crossing the country, with only two days to rest and recover before the meet.

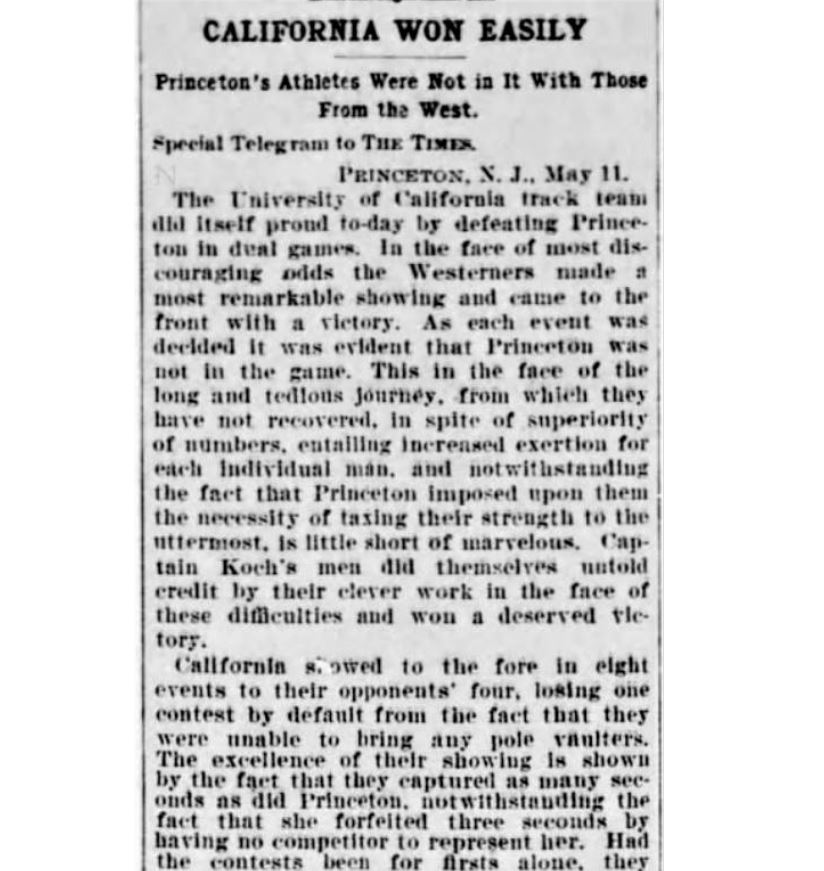

The consensus in the East was that the Californians did stand much chance of beating a strong Princeton team. They were widely underrated, since the easterners knew almost nothing about western teams, and tended to look down on them on principle. The rules for the Princeton meet were also unfavorable for the Blue and Gold. Princeton insisted that points would be awarded for both first place and second place finishers. Since the Californians were only traveling with eleven athletes, in comparison to the 28 competitors for Princeton, the Blue and Gold would be at a distinct disadvantage. Several athletes had to compete in what were not their regular events. And in at least one case, pole vault, the Californians had to default, as they did not have a pole vaulter among their group.

Despite all their disadvantages, the Cal team performed magnificently. They won eight of the twelve events (including the forfeit in pole vault). They also scored second place in six of the twelve events, despite having to forfeit second place points in three events, because they lacked sufficient athletes to compete. The easterners were stunned. The Philadelphia Times reported:

“The University of California track team did itself proud today by defeating Princeton in dual games. In the face of the most discouraging odds, the Westerners made a most remarkable showing and came to the front with a victory.”

Thus the upstart team from the West, despite all their disadvantages, pulled off a huge win in the first athletic competition ever held been any teams from the west and the east. When news of this victory reached home by telegraph, followed by Robert Edgren’s reports in the Examiner, there was unbridled joy in Berkeley and throughout the Bay. A week later the team took on one of the best teams in the country, the University of Pennsylvania. They put on another great showing, but were trailing going into the final event, the 440. This was not Fred Koch’s best event, but he somehow pulled off a win, ending the meet in a 7-7 tie. Unfortunately, runner Melville Dozier suffered a strained tendon during the Pennsylvania meet, further limiting the number of California competitors.

Nevertheless, the Blue and Gold would compete in six more meets during their seven-week tour of the country. This included a 59-39 blowout of Union College in Schenectady, New York and, on the trip home, both a 55-43 victory at the University of Illinois, and a massive 62-22 win in Denver over what was billed as “all of Colorado.” They also won a large, multi-team meet in Chicago, outscoring Michigan, Wisconsin and several others, despite again being severely outnumbered in competitors against several other schools. As Robert Edgren reported to the Examiner:

“Today, the athletic team of the University of California scored the most decisive and glorious victory of its brilliant career. . . . The teams from the other colleges far outnumbered the one from the Pacific Coast. Wisconsin sent twenty-eight men. Michigan entered twenty and other colleges were represented by teams equally strong in numbers.”

Edgren added, “tonight the California boys own the town, and everywhere we hear their college yells, invariably ending with a whoop of ‘California! California!'” The team received a silver trophy and was proclaimed, “Western Champions.”

The final contest in Denver included perhaps the most surprising moments of the entire trip, when a group of Stanford supporters showed up to cheer the California team on. The Examiner reported: “A group of nine Stanford students howled themselves hoarse whenever a U.C. came in front. And they kept the U.C. yell booming throughout the whole afternoon.” Robert Edgren expressed, “our thanks to our friendly rivals.”

By the time the trip ended, three California athletes held new American records: James Scoggins in the 100 yards, Ernest Dyer in the 120 yard hurdle, and Robert Edgren in the hammer throw. Edgren noted in the Examiner that the team was headed home with their Golden Bear banners, “covered with glory, to be put up in our college library never to be taken out until a U.C. again crosses the continent to battle for its alma mater.”

The team was due back in home on June 27, and the Bay Area began planning a celebration. They were met by hundreds of people at the Oakland train station and escorted to the Olympic Club in San Francisco by ferry, including a torchlight parade in San Francisco led by Cal students, followed by a grand banquet. When they arrived at the station, Cal English Professor Charles Mills Gayley took special notice of the Golden Bear banners, leading him to write a song entitled, “The Golden Bear,” with lyrics referencing to “Our silent, sturdy Golden Bear.” The song became an instant hit in Berkeley and, together with the track and field team’s spectacular triumphs and their Golden Bear banners, it gave birth to a new nickname for the University.

As for hammer thrower and Examiner reporter Robert Edgren, he went on to become Cal’s very first Olympian, competing in both discus and shot put in Athens in 1906. (For the only time in history there was an interim Olympics in 1906, coming between the St. Louis games in 1904 and the London games of 1908.) Edgren went on to become a very highly regarded professional sportswriter.

And it is because Robert Edgren and the rest of the glorious 1895 Cal Track and Field team that I am able to end this story by saying:

GO BEARS!