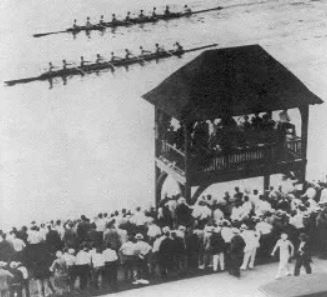

In 1960, the Helms Athletic Foundation reviewed the records and accomplishments of the best college football teams from the beginning of the sport in 1869 to the end of the 1959 season, to decide which team was the greatest of all time. Their answer? The 1920 University of California Golden Bears. Undefeated and untied, they outscored their opponents by a combined score of 510-14. The season was capped off by a 28-0 thrashing of favored Ohio State in the Rose Bowl. Midway through the season, San Francisco Chronicle writer and former Cal football player Clinton “Brick” Morse wrote that they were “a Wonder Team.” Although Cal Coach Andy Smith was unhappy with the hype, the nickname stuck.

In honor of the Wonder Team, we are going to post the story of each of their nine games on the 100th anniversary of the date it was played.

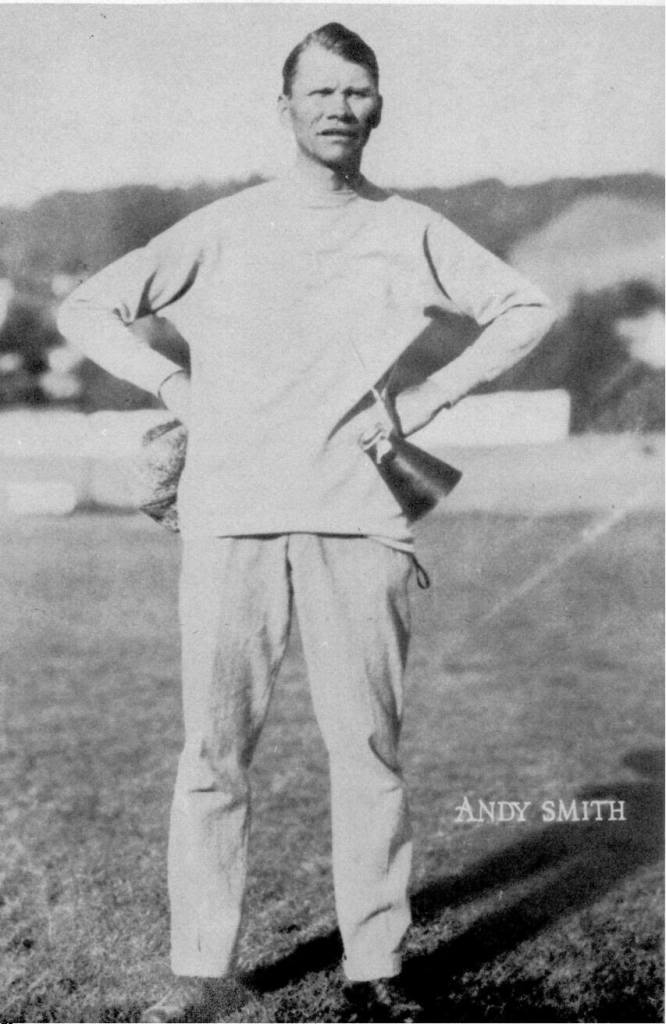

Prelude: Andy Smith Comes to Berkeley

Although the University of California began playing the sport of football in 1882, it abandoned the sport in favor of rugby after the 1905 season. Under the rules of the time, football was extremely dangerous and a number of college players had been severely injured and even killed on the field. Stanford, USC and several other west coast schools joined Cal in making the switch. But after the 1914 season a dispute developed between California and Stanford over the eligibility of freshman players. After a series of increasingly acrimonious negotiations, the schools broke off all athletic competitions between them. This left California looking for a substitute rival, and it turned to the University of Washington. But there was a problem: Washington played American football. The rules of American football had been changed substantially since 1906, making the kind of severe injuries that had occurred in the early days of the sport much less common. And so, just like that, Cal went back to playing American football in 1915.

This created another problem, however. California had a great rugby coach, Jimmy Schaeffer. But he knew almost nothing about football. He did manage to coach the team to a very respectable 8-5 season in 1915, although there was an embarrassing 72-0 loss to Washington. For the 1916 season, however, Schaeffer himself offered the Cal job to a young coach at Purdue, Andrew Latham Smith. Smith accepted, and headed to Berkeley for the 1916 season.

Smith’s first two seasons at Cal were solid, but unspectacular. The team went 6-4-1 in 1916 and 5-5-1 in 1917, playing several games against teams like USC and St. Mary’s, who were also making the transition back from rugby to American football. 1918 provided the first inkling of possible greatness. The Bears’ 7-2 record was good enough to win the championship of the fledgling Pacific Coast Conference and they beat Stanford, which had just decided to start playing football again, by a satisfying score of 67-0.

1919 was another good season, with the Bears going 6-2-1, including wins over USC and Stanford. But the real excitement that year came from the freshmen. At that time, freshmen were not eligible to play on the varsity squad and had their own separate team. Andy Smith had hired a new assistant in 1918, former Cal rugby player Clarence “Nibs” Price. Price, who had coached high school football in southern California before serving in World War I, had already been instrumental in encouraging Albert “Pesky” Sprott, Stanley Barnes, Cort Majors, and several other outstanding players to attend Cal. Now he brought even more outstanding recruits to Berkeley, including Harold “Brick” Muller, Archie Nisbet, and Bill Bell, all of whom played on the 1919 freshman team. That team went 11-1 in 1919, with the only loss being a one-point heart-breaker against Nevada. And they pounded the Stanford freshmen 47-0. With this group of players now eligible for the Varsity team, it looked like 1920 would be a very good season for the Bears. As it turned out, “very good” wouldn’t be the half of it.

Andy Smith Picks His Team

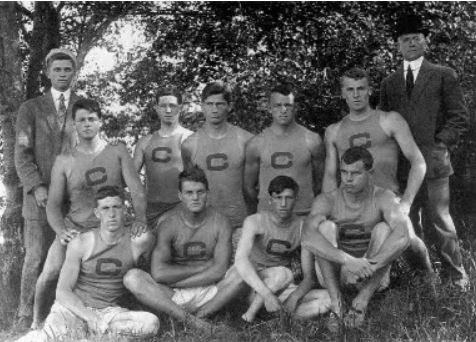

In that much more casual era, the Golden Bears’ 1920 football practice started on September 15, just 10 days before the scheduled season opener against the Olympic Club. On that day Coach Smith issued a general call to the student body for anyone interested in playing football to show up and try out for the Varsity team. In addition to the 13 letter men returning from the 1919 varsity team and the players from the freshman team, nearly 300 other students showed up for try outs. Coach Smith rapidly dismissed over 200 aspiring football players before dividing the remaining players into teams based on their class years. After a few days of practice, formal games were played. The Seniors beat the Juniors 14-0, while the Freshmen upset the Sophomores 7-0. Then in a “Class Championship” game, the Seniors disposed of the Freshmen 14-7. The third place game was a 38-7 rout by the Juniors over the evidently dispirited Sophomores.

Once these class games were complete, Coach Smith announced the names of twelve players he said, “would form the nucleus of the varsity squad.” Twelve no doubt seems like a paltry number of players to a modern fan, but in those days of extremely limited substitutions, when all players were expected to play both offense and defense, it was not unusual for the starting eleven to play every snap of a game.

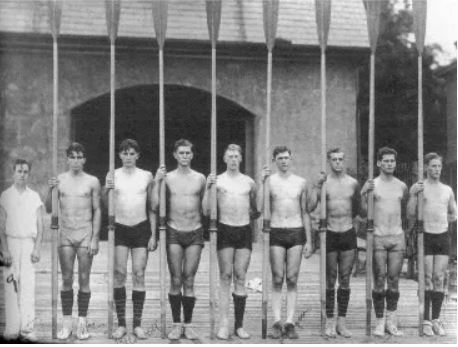

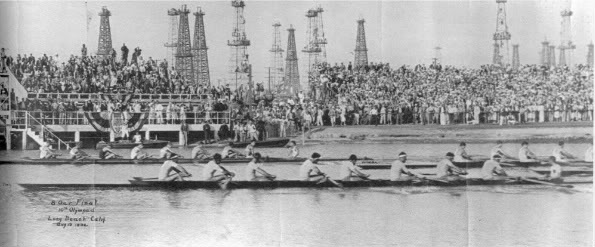

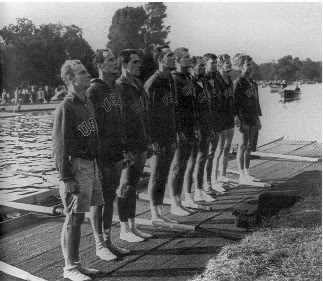

The players announced by Coach Smith included several who would be at the very heart of the Wonder Team, Archie Nisbet, Irving “Crip” Toomey, Jesse “Duke” Morrison, Dan McMillan, Bob Berkey, George “Fat” Latham, Cort Majors and Lee Cranmer. Smith noted that “other men would be added to the squad” as they proved themselves in practice. There can be no doubt that Smith had in mind Albert “Pesky” Sprott, a star of the 1919 team. Sprott had missed the pre-season try outs since he had just returned from the Olympics in Antwerp, where he finished sixth in the 800 meters. And Smith was also counting on another returning Olympian, Harold “Brick” Muller. Muller had excelled on the 1919 freshman team before heading to Antwerp to win a Silver Medal in high jump. Smith knew Muller had an amazing arm and was already drawing up plays for him.

The Olympic Club

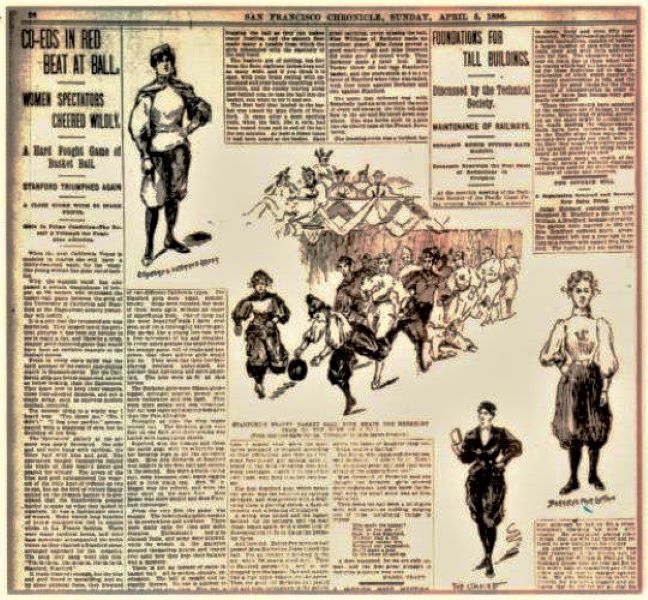

In the early years of Cal football, the boys in Blue and Gold (they didn’t become “Golden Bears” until 1895) had no nearby colleges or universities to compete against. Therefore, their opponents consisted entirely of teams fielded by local amateur athletic clubs, mostly from San Francisco. The Olympic Club, a private social and athletic club, was founded in San Francisco in 1860. Although it is now an exclusive and expensive club, best known for its golf courses, in 1890 it began sponsoring a football team, known by the nickname of the “Winged O.” Always on the look-out for worthy opponents, Cal Football began playing the Olympic Club in 1892. Eventually the Olympic Club would also play regularly against schools like Stanford, Santa Clara and St. Mary’s, all the way into the 1930s.

There was a whiff of a scandal associated with the Olympic Club team right at the outset. In 1890, other amateur athletic clubs accused the Olympic of luring the best players onto its team by offering them jobs. An investigation was undertaken by the Amateur Athletic Union (“AAU”). It concluded that the Olympic Club was indeed giving jobs to players, but decided this did not make those players true professionals. The AAU coined the term “semi-professional” or “semi-pro” (the first known use of these terms) to describe the Olympic Club players and determined that it was acceptable for such players to compete in amateur leagues.

The Game

Cal’s first game of the 1920 season was set for September 25 at California Field on the Berkeley campus. Classes would not start until the following Monday, and a modest crowd was expected for a relatively low-key match-up. While the Bears had only selected their team a few days earlier, the Olympic Club already had two games under its belt, a 7-0 loss to Santa Clara University and a 26-13 win over the Mare Island Marines, a team fielded by the naval base in Vallejo.

On the morning of game day, the San Francisco Chronicle‘s Dick van Horn told his readers: “The Olympic Club, like all the rest of the football teams hereabouts, is raising the cry, ‘Beat California,’ and will try to live up to the cry today.” Van Horn noted that the Bears had suffered injuries in practice and said, “Andy Smith has had quite a hard time picking his first squad owing to the fact that injuries have taken several men off his squad.” He proclaimed the Olympic Club team to be one of its best ever, and added, “the Winged O warriors have a pretty fair chance of holding, if not beating, the Blue and Gold.”

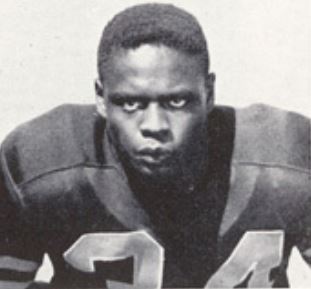

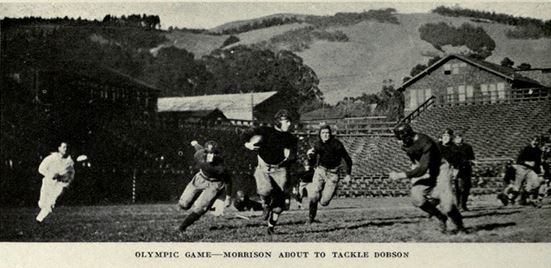

As might have been expected of players who had only begun practicing as a team a few days earlier, the Bears got off to a slow start. The game was mostly a defensive battle. According to Doug Montell of the Oakland Tribune, “practically the entire game was marked by a punting battle between Morrison of the Bruins [i.e., the Bears] and Dobson of the Olympic Club, in which the Blue and Gold kicker finally came out on top.” The Chronicle‘s van Horn described the first half as “a poor spectacle. It was kick, kick, kick – first California and then the Olympics.” He did commend the strong defense of Cal’s Brick Muller describing the first half as essentially, “Brick Muller versus the Olympic Club, for Brick stopped practically every play during this time.”

Late in the second half the Bears, in van Horn’s words, “began to play a little football.” A big hit by Brick Muller and Bob Berkey forced the Winged O’s star, “Chaff” Charlton, to fumble a punt, and Muller recovered the ball at the Olympic Club 25-yard-line. Two plays later, Cal’s “Duke” Morrison went around left end to score. Toomey kicked the extra point and the Bears went into halftime with a 7-0 lead. Captain Cort Majors warned his teammates not to be complacent. “Okay gang,” he told them, “the score’s nothing-to-nothing. Let’s go to work.” That phrase became the Wonder Teams’ unofficial team motto for the next five seasons.

It was thus the aspect of the game now called “special teams” that led to the first California score. The term “special teams” was not used in 1920, since the same 11 players were on the field for every play, including punts and kicks, as well as offense and defense. So there were no “special” teams, but rather the same team.

The second half remained primarily a defensive struggle, but the Bears began to show strength in what today would be called the “red zone,” both on offense and on defense. As the Chronicle‘s van Horn described it:

The [Olympic] Clubmen made their yards when least needed, that is in the center of the field they went through for ten and twenty yard gains, but when they needed the yards, the California men blocked them up to a standstill. And on the other hand, the California team made its yards when needed, and once inside the ten yard line, nothing could stop them.

In fact, the Olympic Club out-gained California that day by an almost 2-to-1 margin. But every time the Winged O got close to scoring, the mighty Golden Bear defense rose up to stop them.

The Golden Bears’ next score, in the third quarter, resulted from an nice combination of offense, defense and “special teams” play. A long California drive ended in a turnover on downs at the Winged O’s 1-yard-line. Switching to defense, the Bears stopped the Olympic Club from making a first down, forcing a punt from their own end zone. Crip Toomey ran the punt back to the 15 and three plays later Duke Morrison was able to plunge through the Olympic Club line from the 8, for his second touchdown of the day. Switching to his role as kicker, Toomey added another extra point. As the Chronicle‘s reporter described it, “all through the second half, the big hole in the Olympic Club was through center and the guards.” [Note: that seems like a very big hole!]

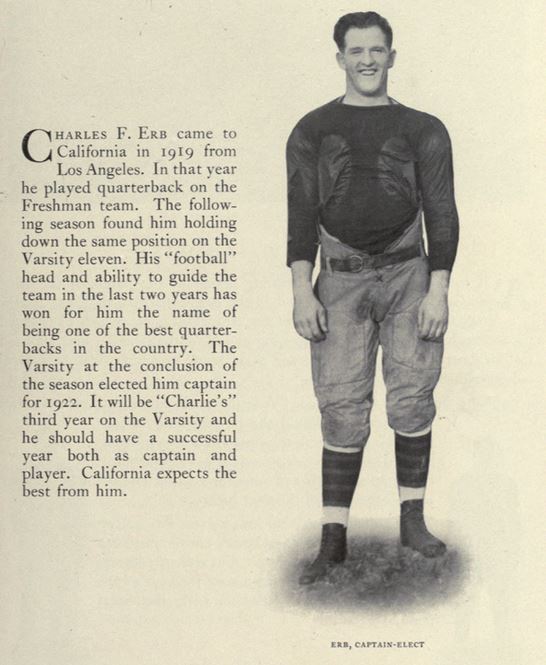

Trailing 14-0 in the fourth quarter, the Olympic Club’s coach decided he had no choice but to go all-in on the passing game – a still unusual and high risk strategy at the time. The Winged O had some success, completing several passes before disaster struck – a pick six by Cal’s Charly Erb. As the San Francisco Examiner described it:

The final score was as pretty a bit of interception as could be wished for. Charlton gave the signal for a Club forward pass and Dobson sent down a pass fully twenty yards, but Erb of the Varsity jumped high in the air and took the ball and bolted down the field for a 60-yard run to a touchdown.

The Chronicle‘s van Horn reported Erb’s interception return as 70, rather than 60 yards. The Oakland Tribune‘s Montell called it 80 yards. In any event, it was long. Certainly much longer than the 20-yard forward pass by the Olympic Club that preceded it – a distance the Examiner writer clearly found impressive for a pass. Before their season ended, the Bears would change the thinking about what constituted an impressive distance to throw a pass.

Final score, California 21, Olympic Club 0. Bay Area sportswriters heaped praise on Charlton and Dobson of the Olympic Club, and the San Francisco Examiner singled out Cal’s Duke Morrison and Brick Muller as “phenoms.” It was a solid win for Andy Smith and his Bears, especially considering how short a time they had been practicing. But it was certainly not spectacular. The Chronicle‘s van Horn opined that the Bears were “still weak in the aerial line,” i.e., the passing game, but found that to be their only significant weakness, at least once they got past a jittery first half.

The Oakland Tribune‘s Doug Montell was more effusive. He agreed that the Bears had played a “mediocre brand” of football for most of the first half, but found that they had really “come alive” in the second half. He believed that “Andy Smith’s warriors showed real knowledge of the great collegiate game of football,” and that considering it was their first game of the season, against one of the strongest Olympic Club teams in years, “the victory of the Blue and Gold is taken as an indication of great strength for the coming Coast Conference season.” The win may have been more impressive than it seemed, as the Olympic Club turned out to be a pretty good team that year. Two weeks later they would beat Stanford 10-7.

The first game had been played. The 1920 California Golden Bears were 1-0. It was a good start. But how good were they really? Stay tuned!